How to Handle a Shaman?

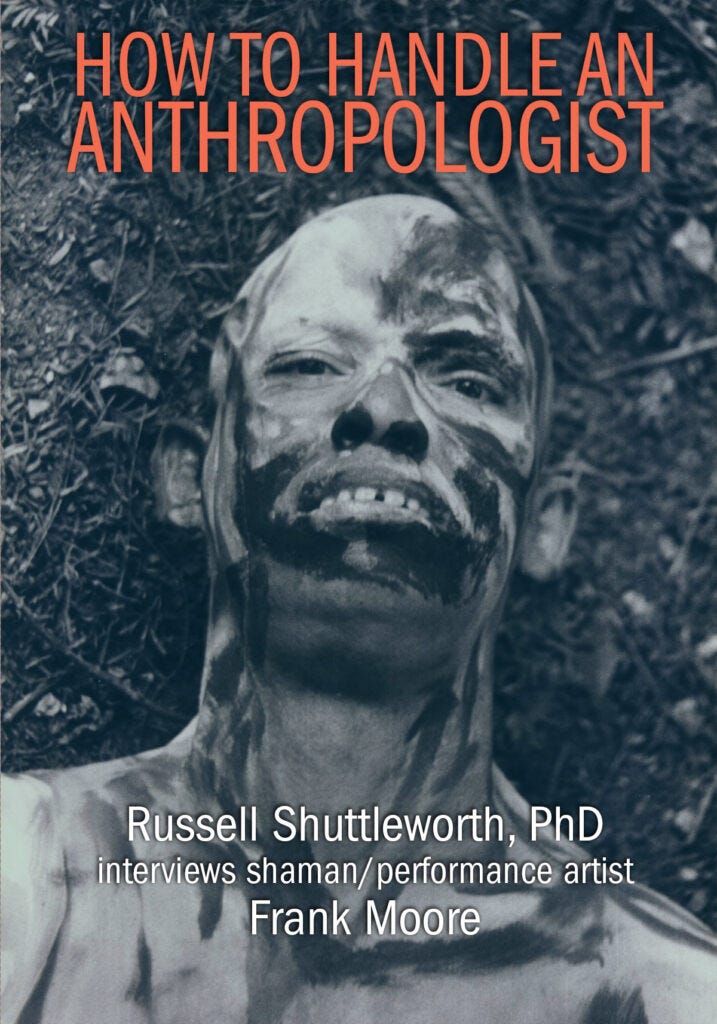

Written for the book, How to Handle an Anthropologist: Russell Shuttleworth, PhD interviews shaman/performance artist Frank Moore.

How to Handle a Shaman?

By Russell Shuttleworth

The line between the art and life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible.

Allan Kaprow 1966

The infamous performance artist Frank Moore died of pneumonia on October 14, 2013. This was a huge loss to the performance and avant-garde art community. Frank had been a staple of this scene since the 1970s. Adept at a wide range of expressive arts such as poetry, painting and film-making, it was his performance art that he will likely be most remembered for. He was heavily influenced by the performance art that emerged in the late 1950s through the 1960s—spontaneous and non-linear performances exemplified by Allan Kaprow’s Happenings (1966). But Frank’s often long performances--up to 48 hours--could stir controversy. As a National Endowment for the Arts funded artist in the 1990s, he was even targeted by the arch-conservative Republican senator Jesse Helms. Why? Frank performed in the nude, usually with the assistance of several helpers who were also unclothed. As the performance progressed, it was common for many audience members to disrobe and participate in the sensual movements and rubbing of bodies. Although these performances were undoubtedly erotically charged, many people incorrectly label them as pornographic. It is hoped that the following series of interviews I conducted with him from 1997-2009 will provide sufficient context to more fully appreciate his celebration of eroticism and creative vision for art and living. These interviews provide an articulate and detailed chronicle of important events in Frank’s life, his intimate relationships and artistic endeavors up through the late-1980s. They also often morph into conversations we had on a wide range of topics—for example, current affairs, historical events, posts to Frank’s listserv or one of his recent performances. These interchanges interweave into and out of Frank’s telling of his life story.[i]

First Meeting and Interview Process

I first met Frank Moore in recruitment efforts for ethnographic research I was conducting for a doctoral degree in medical anthropology. I was researching the search for sexual intimacy by men with cerebral palsy (Shuttleworth, 2000).[ii] A girlfriend at the time told me she was friends with a social worker who was a caseworker for a disabled performance artist who performed in the nude and who might want to talk to me. She also told me that her niece had seen this man, who used a wheelchair, hanging out at Sproul Plaza scoping out and approaching women on the UC Berkeley campus. My girlfriend’s niece had described him as “kind of sleazy.” Her description immediately struck my interest. This performance artist, a man named Frank Moore, certainly sounded bolder than the few men I had so far interviewed for my research. Luckily, I was able to secure his telephone number from the social worker. Little did I know at the time that my interviews with him would challenge the parameters of my understanding of disability and the meaning of research.

At the beginning of the first interview, one of Frank’s helpers led me into his studio at the back of his house where another helper was setting up a video-camera. It turned out that Frank wanted to tape all the interviews for his own use (he videotaped the first eleven interviews and audiotaped the rest)! Later on, I found out that Frank had been documenting all of his projects for years. Even later on--I came to understand Frank’s telling of his life story and our ongoing conversation as the creative vehicles they were. With our respective recorders turned on, Frank started the interview by saying that he was going to title the book, How to Handle an Anthropologist! I thought this was funny at the time and not to be outdone quickly replied, “Shaman!” In retrospect, this beginning was a clear sign that if I thought I was simply going to be doing a few interviews with Frank about his sexual relationship history, my short-term ethnographic intentions would be subverted.

For each interview the process was similar. I would arrive at Frank’s multi-colored house at the agreed upon time. Mikee or Linda, the two helpers referred to above and the two most central members of his tribe (there were three other members), would usher me inside. Frank would usually be sitting in his wheelchair typing at his computer, which was situated at one of the front windows looking out into the street. We would all greet each other and then Linda or Mikee would lead me to the studio, which was located at the back of the garden, and I would sit down in the chair and wait for Frank to make his appearance. For a few moments, I would sit silent, enjoying the calm before the storm and gaze up at Frank’s oil paintings, which adorned the walls: a series of nudes in various poses. Of all of Frank’s art, I most enjoyed these paintings. Frank told me he had painted them with a brush attached to his head pointer. Their jagged immediacy always made them come alive and in the flesh beckoning me.

Mikee or Linda would then wheel Frank into the room within a couple of feet and face him toward me. Our respective recorders would be turned on to capture the interview. Frank communicated using a head pointer and alphabet board. I would spell out the letters and words Frank indicated, and often repeat the entire sentence or two back to him to make sure it was correct. I had grown comfortable with the slowness of this form of communication while working with other people who used it. Frank’s alphabet board was pointed with the letters upside down to him but right side up to those he was talking with. This was different to the way I had seen people using an alphabet board before with the letters pointed toward themselves and right side up. That meant for a person talking to Frank and interpreting his board, they could be with him face-to-face instead of having to read his board upside down or be by his side reading it. He told me that this set-up, along with the slowness of communication itself, enhanced intimacy, as it focused the conversation, was more comfortable for other people and also drew the person toward him. As I was to find out, in effect this process was a powerful way to deepen and intensify the interviews.

Being face-to-face with Frank combined with the slow pace of the interviews also allowed me a space to closely interrogate his words and phrases. I would ask layer upon layer of questions in order to understand everything Frank expressed, rephrasing what I thought he meant for verification. Frank could sometimes be quite cryptic in his expression, to some extent perhaps a function of the way he communicated, but I think he also enjoyed the chase, as I was often one step behind what he actually meant. At any rate, I believe my doggedness paid off, as more often than not I was able to draw out the meaning behind his words. In reading this book, it is good to keep in mind the process of communication for the interviews in order to get a sense of their rhythm. That being said, the length of time varied from about one and a half to two and a half hours and usually ended up producing 10-15 pages of transcripts.

Eros and Creation

Many people like my friend’s niece immediately placed Frank in a sexual box. Since nudity formed a major part of Frank’s performances ipso facto sex must be at the core of his raison d’etre. In fact, sex with the goal of orgasm had been removed from the equation. Taking off one’s clothes was first and foremost a way to begin peeling off the layers of normative expectations people have of both others and themselves, a way to open up to the creative possibilities that normality tends to stifle or extinguish. Sensual, bodily play without the goal of orgasm or what Frank termed eroplay was a central part of both his public and private performances. He saw eroplay as an avenue for connection and relational bonding beyond societal norms and masks, ostensibly on a sensual, physical level but also on emotional and other levels of experience. A good performance saw the dissolution of egos and a sense of intimacy form between individuals and the group. For Frank, playing together in such a way helped to counter the sense of isolation and alienation that he saw endemic in modern society. Frank’s own sense of isolation experienced at times during his youth had galvanized a desire to be close with people as he got older; and although he enjoyed the physical sensuality of eroplay, he also grew to place a high value on nurturing intimacy and community within these performances and in fact in all areas of his life. Perhaps here it would be good to let Frank himself explain more in depth what eroplay is and how he employed it in his creative work:

Eroplay is intense physical playing and touching of oneself and others. Eroplay is the force or energy released by such play. It is also the happy, playful attitude toward life that comes from such play….Foreplay leads to orgasm--eroplay leads to being turned-on in many different ways and in all parts of the body--including, but not limited to, physical arousal….eroplay is the blissed-out, warm, relaxed, turned-on, totally satisfying feeling of a good head rub. Eroplay is fun! Eroplay is innocent and childlike… Eroplay decreases isolation and alienation. It increases self-trust and trusting of others. It makes you harder to be controlled. Eroplay leads to a life-style with all these characteristics. The life-style looks strangely like the love generation, but without drugs or free sex….What I am doing is taking nudity and acts that are usually considered sexual and giving them a new, nonsexual context. That creates a tension, a conflict, an examining, a leap into something new. That is what I am after….By taking sexual acts and sincerely putting them into a different context, I create another reality, another way of relating. I also create conflict with the normal reality--and that conflict may change, in an underground sort of a way, the normal reality. I think art--or at least this kind of art--should create conflict and change (Moore, 129-130: 1989).

All of Frank’s creative endeavors, not only his public and private performances, were meant to disrupt the mainstream and/or expand the particular art form. For example, his poetry can often be raw and confronting, his band the Cherotic All-Stars stretched the boundaries of musical performance and his internet radio station LUVeR hosted a range of politically radical shows and DJs playing multi-genre tunes. After finding out that I loved blues, psychedelic rock and garage rock, Frank invited me to DJ for two hours a week on LUVeR. For several years, the gruvemeister held court weekly over the musical abyss--Dr Gruve’s Psychedelic Blues & Boogie Revival! Each week’s playlist was approached artistically--where continuity of themes or styles between contiguous songs or interesting juxtapositions were the keys to an engaging set. Upon hearing that I played blues harmonica (not that good at the time I must admit), Frank also invited me to play in his band, Frank Moore and the Cherotic All-Stars. And for quite a few years I honked with the band at gigs in established SF Bay Area punk clubs, hole-the-wall venues and sometimes at Frank’s own house. By generously encouraging me and providing the opportunity to play music in several of his initiatives, Frank helped me reconnect with the muse.

Frank in fact had a generosity of spirit when it came to encouraging artists or would be artists, especially those struggling outside the mainstream. Frank hosted a listserv for underground artists of all persuasions. He would solicit artists and musicians’ work, uploading images to special artist galleries on his website or spinning their self-made cds on his radio station. He would invite artists and musicians to play at his gigs and performances, no matter if you had just picked up the instrument or were a seasoned pro. On Frank’s show, the Shaman’s Den, he interviewed artists, political activists and generally those people who had something to express outside the norm, which was beamed once a week from his house on Sunday evenings.

I played harmonica with Frank Moore and the Cherotic All-Stars from 2001 or so until 2007 when I left the Bay Area for Sydney, Australia. These shows often started similarly with Frank nude on stage in his wheelchair. He would sit gazing out into the audience and singing to them for 5-10 minutes--what sounded to untrained ears like some alien scat singing. Frank, of course, was well aware of the visual and audial shock that seeing him naked in his wheelchair making unrecognisable sounds would have for many in the audience. One by one, the musicians would join Frank on stage and begin playing their instruments. Several members of the tribe would also join him on stage naked, moving their bodies sensually to-and-fro. The interplay between the various musicians and the dancers was sensual and raw. Depending on who was playing, what they were playing and the combination of sounds--the music could go anywhere. There were literally no musical boundaries and the sound would gradually morph from slow and light to fast and heavy, soft to loud. The effect on me was mesmerising and for the duration of the performance I was hooked into what the group and I were creating in the moment. Formless but forming, this kind of creative movement in the moment was the goal or should I say the lack of goal in all of Frank’s performances and creative expression in general. Having a goal for Frank actually destroyed the artistic spirit. It was the lack of a goal that opened up creative possibilities. The very process of creation for Frank was the art.

The Disability Rights Movement and the Personal is not the Political

Coming of age in the mid-to-late 1960s, Frank successfully took advantage of a crack in the normative egg that opened up alternative experiences and over the years forged a unique orientation within his art and lifestyle. In the latter part of that decade while in college, he had written a radical column in a community paper advocating for progressive political, social and cultural change. During the 1970s and 1980s, the major time period from Frank’s life that are covered in this book, he concurred with the struggle for disability rights, and he could at appropriate times, be an activist in the traditional sense of the term. Frank, in fact, was one of the 150 protesters, disabled people and their allies, on April 5, 1977 who occupied the federal building in San Francisco, trying to enforce the issuing of regulations for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. This was one of many protests across the United States, but the only one that lasted 25 days!

But whereas for many in disability rights movement, political struggles and personal struggles were inseparable, Frank refused to take up, the feminist mantra of the personal is the political in its strictest sense. Although he could certainly relate to being the brunt of disability prejudice and exclusionary practices himself and was willing to put himself on the line in cases such as the 504 protests, Frank believed living one’s personal life as if it were in continuous reference to oppressive social structures limited human potential and to some extent validated these structures. From his perspective, playing the victim role in one’s personal life often engendered an inability to take risks—and taking risks was essential for the kind of creative lifestyle he was forging.

Similarly, the disability rights movement often held Frank at a distance. The movement, of course, could not deny his role in opening up a space for disabled artists, but it tended to disavow his actual performances. Perhaps too close of an alliance with Frank’s perspective may have seemed like too high of a risk, perhaps a liability, in the movement’s efforts toward inclusion. And although some disabled artists and activists did glimpse the radical, transformative potential of his work, unsurprisingly, most saw Frank’s focus on erotic play as narrowly slotting into the sexual box: “Wasn’t it just his way of getting the girl(s)?”

The disability arts scene began to really flourish in the 1990s, with much of the art implicitly if not explicitly referring back to its origins in disability. Although he acknowledged this art scene and the artists within it, Frank saw himself as first and foremost an artist, not a disabled artist. This is not to say he ignored the fact that being disabled provided him unique opportunities to express himself. In fact, he often said he was lucky to be born as he was with cerebral palsy because it enabled him to more easily take on the role of a transformative force. And he often used his impairment and disability in his work to shock and subvert what he saw as an oppressive normative reality. But Frank believed that continually referring back to his impairment and disabling social structures would limit his art and miss the larger spectrum of human expression.

Frank, it seemed, was often out of step with the disability rights movement. Another point of contention can be seen in his approach to personal assistance. An early experience with a personal assistant pulling a gun on him, was the first and last time he viewed ‘personal assistance’ in economic and transactional terms. Dispensing with seeing this relationship as primarily one of employment, he came to the insight that people actually ‘needed’ to help others. This understanding gave Frank the courage to take a risk and travel across the United States by himself, picking up people who were willing to assist him along the way. When I began interviewing him in 1997, his tribe had been providing him with the help he needed in his daily life for many years. While these services were paid for by California’s In-Home Support Services, this money was thrown into the tribe’s kitty as simply one person’s contribution in getting all their basic needs met.

Frank had grappled with feeling he was a burden on others when he was younger, but he had totally banished the idea that he was burden during his 20s. He came to view his need for personal assistance as relational to others’ needs within the group. On one occasion, government funding was on the verge of being slashed for California’s In-Home Support Services, Frank recognized that a cut in the funding of this program would negatively impact many disabled people’s lives, but he also told me during one of the interviews that this revealed the fragile reality of relying on the system for support. Aside from a diminishment of income, it would not affect the ability to get his support needs met.

With my social science training, I would sometimes challenge Frank for not focusing more on the structural disadvantages that disabled people contend with. After all, many were in dire straits and I thought taking personal risks would have minimal effect on their situation. What of the disabled person who had grown to adulthood in an institution and who had not had any support to be able to leave? Frank knew, of course, that this situation was common. Although never living in an institution, he had known social isolation when he was younger. He had not only written a poem about breaking out of isolation, one of his films also had this title. On several occasions during our talks, Frank conceded that risk-taking was likely more difficult now. In one interview, knowing about the barriers to sexual expression that existed in long-term care institutions and group homes, he brought up the idea assembling a group of sexual facilitators to visit the disabled people living there and provide them with erotic and sexual experiences.

How to Handle a Shaman? The Legacy of Frank Moore

After my doctoral dissertation was submitted, I provided Frank a copy to read. I was feeling apprehensive as I drove to our next interview, not quite knowing how he would react. One thing I was worried about was how one of the other research participants who knew Frank many years previously had characterized his scene as a possible cult. This portrayal was countered by yet another participant who also knew him during this time and in fact had spent several years performing with him. The latter participant talked about Frank in glowing terms and as ahead of his time. In my dissertation, I presented these conflicting narratives to show how people’s interpretations of the same context and experiences can be radically different in order to ethnographically highlight the Rashomon effect.

When I got to his house and asked him what he thought of the dissertation. Frank broke out in peals of laughter. Was he tickled that someone had seen him as leading a cult? What in fact was most amusing to him was I think the mass of concepts I had galvanized to make my points. Frank said that I should dispense with the anthropological and theoretical framing, that the narratives by themselves were powerful. I was caught off guard with this reaction. It was not that I disagreed with him about the power of these men’s stories. But I was not willing to question then that my theoretical framing had added to our understanding of these men’s experiences. After all, exploring these men’s sexual issues with an anthropological lens was the reason for conducting the study in the first place. Yes, anthropology strove to get the insider’s perspective but interpreting this view with theory was also a requirement. It was imperative that I strut my stuff in the dissertation. Frank added that he thought I had captured his perspective well, which at the time was not very consoling.

As the years passed, however, I resonated more clearly with what Frank was saying. Although not totally eschewing theory, I came to more clearly appreciate how it can sometimes get in the way of understanding. Perhaps more importantly, I also came to see that my engagement with Frank in these ongoing interviews transcended any concrete goals or writing projects planned. While I included snippets of his story and perspective in several academic papers I wrote, I gradually let go of the desire to obtain a ‘use value’ from his narrative and gave myself up to the immediacy of the process playing out between us. Letting the process between us take its course led to all kinds of interesting discussions and insights.

There are those who might criticize some of Frank’s methods. In his public and private performances he could sometimes play the trickster, withholding information or secretly planting actors in the audience to play various roles. His uncompromising stand for freedom of artistic expression and ethic of creative freedom in his life might feel threatening to some. But there is no denying that on many issues, Frank was indeed ahead of his time: acknowledging the limitations of narrowly claiming disability identity and disability art, valuing interdependence over independence, realising that personal assistance is relational. These and many of his longstanding views have now been incorporated into critical disability studies discourse as important points of discussion (while others have not).

An approach to eroticism influenced by queer and post theories has also recently emerged in critical disability studies, which has begun to perceive of desire less in heteronormative and orgasmic terms--of bodies as fluid, becoming and connecting in the moment, not fixed in modernist binaries such as abled and disabled. There are differences in this approach to eroplay, but there are also important similarities such as decentralising orgasm and focusing on the sensuality of connection. Both also seek to generate conflict with, disrupt and even subvert an assumed and regulatory sexual reality and to forge other ways of erotically becoming. The new millennium has also seen disabled artists, performance artists especially, who are beginning to express themselves and their bodies as desiring and desirable, erotic and sensual. While these performances still tend to fall under an identity rubric of disability performance art, Frank is their important progenitor.

Although he eschewed the trappings of mainstream success, it is hoped that this book will illuminate for a broader audience Frank’s often misunderstood intentions. Frank knew that unless he risked he would not get what would sustain him in life. In the process of risking himself, he forged unique perspectives on eroticism and the relationship between art and lifestyle. He encouraged others to approach their lives with the same sense of risk and openness to unfolding process as he did. Frank’s enduring legacy will be his ethical commitment to the creative spirit in himself and others.

References

Kaprow. A. (1966) Untitled guidelines for Happenings (c. 1965). In Assemblage, environments and Happenings (pp. 188-198). New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Moore, F. (1989) Eroplay. The Drama Review, 33(1), 120-131.

Shuttleworth. R. (2000) The pursuit of sexual intimacy for men with cerebral palsy. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation). University of California, San Francisco and Berkeley.

[i] The interviews in this book are word-for-word as they were transcribed from the video and audio tapes that Frank and his tribe recorded, except for in several places where a word or phrase has been altered to protect confidentiality or reputation. The reader should note that the first of these interviews happened twenty-two years ago and the most recent occurred ten years ago; so my own views may have remained the same or changed on a particular issue.

[ii] All research participants discussed in the dissertation and during these interviews with Frank were given pseudonyms. The original research was conducted in Berkeley and Oakland. The disability community in these cities is quite large in respect to other cities in the United States. Disabled people in this community are often well connected with each other. This is mainly due to the history of the area, with Berkeley being the birthplace of the disability rights movement in the 1960s, and advocacy and other services being provided to disabled people by disability organizations over the years (the Physically Disabled Students' Program which began at UC Berkeley in 1970 and the first Centre for Independent Living founded in 1972).

The research was ethnographic, a highly descriptive methodology, and I mostly used snowball sampling, which were both hurdles to insuring confidentiality. There were also occasions where I hung out with several of the participants socially as part of the participant-observation component of the study. The fact that quite a few of the participants not only knew each other but had hung out together at one point or another in their lives compounded the confidentiality problem even further. As much as possible, I tried not to use quotes that would identify participants. But description of each participants’ degree of physical limitation was unavoidable in phenomenologically exploring their search for sexual intimacy and relevant others’ perspectives. Nevertheless, most participants in the research did not recognize who others were in the end product. In the case of Frank, it seemed nigh on impossible to disguise several participants who were associated with his communal group in the late 1970s and early 1980s, especially when their stint with him formed a significant narrative in their sexual lives. And true to form, Frank guessed correctly who these participants were. One of the chapters in the book documents this discussion. Another interesting point about the men in this research is that almost half asked me to use their real names. However, in the ethics application that was approved by the university I had already committed to trying to keep participants anonymous. The original research funded interviews from 1997-1999 and was assisted by a fellowship from the Sexuality Research Fellowship Program of the Social Science Research Council with funds provided by the Ford Foundation.